The island of Great Britain, often perceived as linguistically monolithic due to the global dominance of English, actually cradles a vibrant and ancient linguistic heritage within its western reaches. Wales, or Cymru as it is known in its native tongue, stands as a testament to linguistic resilience, where the rhythmic sounds of Welsh (Cymraeg) have coexisted, often contentiously, with the pervasive influence of English for centuries. This article delves into the intricate journey of the Welsh language, from its ancient Celtic roots to its modern revival, exploring the historical forces, linguistic distinctions, and societal efforts that define its relationship with English.

An Ancient Tapestry: The Roots of Welsh

To understand the dynamic between English and Welsh, one must first appreciate their divergent origins. English, a Germanic language, evolved from the dialects brought to Britain by Anglo-Saxon invaders in the 5th century, influenced later by Old Norse and Norman French. Welsh, in stark contrast, is a Brythonic Celtic language, a direct descendant of the language spoken across much of Roman Britain. When the Anglo-Saxons pushed west, the Brythonic speakers in what is now Wales became known as "Wealas" (foreigners) to the newcomers, giving the land and its people their English names. The language they spoke, however, continued its own evolution, relatively isolated from the Germanic tide.

This initial separation laid the groundwork for a linguistic chasm. While English absorbed Latin and later French vocabulary and grammatical structures, Welsh remained firmly rooted in its Celtic heritage, preserving a distinct phonology, morphology, and syntax. For centuries, the two languages developed in parallel, with limited direct interaction until the political and social landscapes began to intertwine more aggressively.

The Tide Turns: English Dominance and Welsh Suppression

The Norman Conquest of 1066 profoundly impacted the linguistic map of Britain, establishing Anglo-Norman French as the language of the ruling elite and administration, and further entrenching English as the language of the common people in England. In Wales, however, the Norman incursions were met with fierce resistance, and while castles and Norman lords dotted the landscape, Welsh remained the dominant language of the populace.

The most significant blow to the status of Welsh came with the Acts of Union (1536 and 1543), which formally incorporated Wales into the Kingdom of England. These acts explicitly stated that English was to be the sole language of law and administration in Wales, effectively marginalizing Welsh in public life. The rationale was clear: to assimilate the Welsh into English culture and governance. Section 20 of the 1536 Act famously declared that "no person or persons that use or exercise the Welsh speech or language shall have or enjoy any manner office or fees within this realm of England, Wales or other dominion, lordship, manner or place of the King’s jurisdiction." This declaration was a powerful deterrent, forcing ambitious Welsh individuals to adopt English for social and economic advancement.

Despite this legal suppression, Welsh continued to thrive as the language of home, community, and religion. The translation of the Bible into Welsh in 1588 by William Morgan was a monumental achievement, standardizing the language and ensuring its survival through the centuries. However, the pressure mounted with the Industrial Revolution, which brought significant internal migration within Wales and increased contact with English-speaking areas. English became associated with progress, industry, and opportunity, while Welsh was often perceived as a language of the rural, uneducated past.

The 19th century saw the infamous "Welsh Not," a punitive system in some schools where children caught speaking Welsh were made to wear a wooden placard around their necks, often leading to corporal punishment. This cruel practice, though not officially sanctioned by the state, symbolized the systemic attempt to eradicate Welsh from the educational sphere and instill English as the sole language of learning. By the early 20th century, the percentage of Welsh speakers had significantly declined, leading to genuine fears for its long-term survival.

The Dawn of Revival: A Language Reborn

The latter half of the 20th century marked a dramatic turning point. A burgeoning sense of Welsh national identity, coupled with the efforts of language activists and cultural organizations, sparked a powerful revival movement. Key milestones included:

- Plaid Cymru (The Party of Wales): Founded in 1925, this political party championed Welsh language rights and self-governance.

- The Welsh Language Society (Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg): Established in 1962, this direct-action protest group campaigned tirelessly for the recognition of Welsh in public life, often engaging in civil disobedience. Their efforts led to significant policy changes.

- The Welsh Language Act 1967: A relatively weak act that acknowledged the validity of Welsh in legal proceedings but didn’t establish full equality.

- S4C (Sianel Pedwar Cymru): Launched in 1982, this dedicated Welsh-language television channel provided a crucial platform for Welsh-medium broadcasting, culture, and entertainment, proving that the language could thrive in modern media.

- The Welsh Language Act 1993: This landmark legislation established the principle of equality between Welsh and English in public life in Wales, leading to the creation of the Welsh Language Board and requiring public bodies to provide services in Welsh.

- Devolution and the Welsh Government: The establishment of the National Assembly for Wales (now the Senedd Cymru – Welsh Parliament) in 1999 gave Wales its own legislative powers, allowing for the creation of proactive language policies.

- The Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011: This strengthened the 1993 Act, establishing Welsh as an official language of Wales (alongside English) and giving individuals a right to use Welsh in their dealings with public bodies. It also created the office of the Welsh Language Commissioner.

These legislative and cultural shifts have transformed the linguistic landscape. Welsh-medium education has expanded significantly, ensuring new generations are fluent in the language. Bilingual signage is ubiquitous, and public services increasingly offer a Welsh option.

The Linguistic Divide: English vs. Welsh

Beyond the historical context, the inherent linguistic differences between English and Welsh present fascinating challenges and opportunities for learners and speakers.

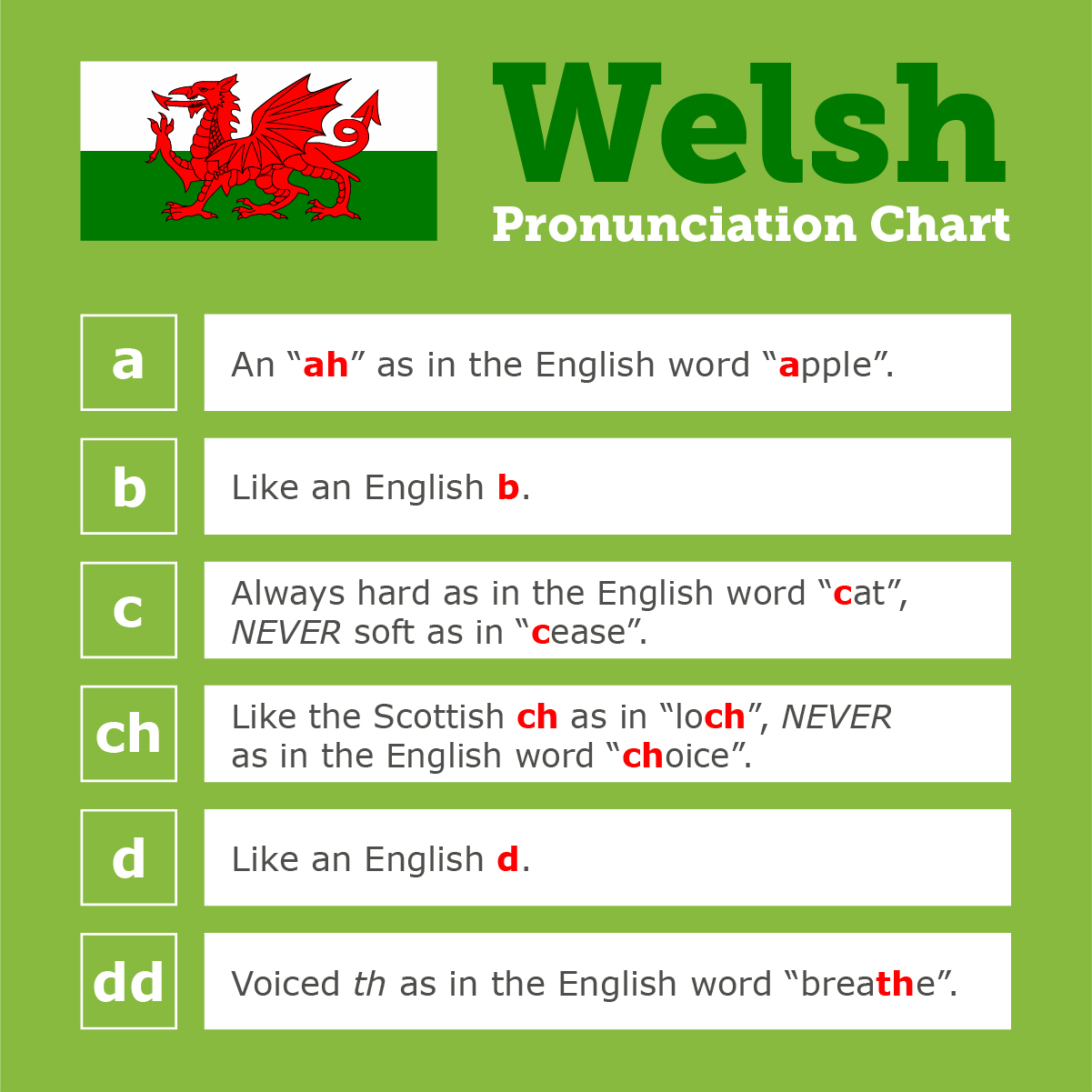

1. Phonology (Sounds):

- Unique Sounds: Welsh boasts sounds not found in English, such as the voiceless lateral fricative ‘ll’ (similar to ‘thl’ but with air escaping from the sides of the tongue), the trilled ‘rh’ (a voiceless ‘r’), and the guttural ‘ch’ (as in Scottish ‘loch’).

- Vowels: Welsh vowels are pure and consistent, unlike the often diphthongized English vowels (e.g., ‘a’ in Welsh is always like ‘ah’).

- Stress: Stress in Welsh words generally falls on the penultimate syllable, a predictable pattern that contrasts with the often unpredictable stress patterns of English.

2. Morphology (Word Structure) and Syntax (Sentence Structure):

- Initial Consonant Mutation: This is perhaps the most striking feature of Welsh. The initial consonant of a word changes depending on the preceding word or grammatical context (e.g., tad (father) becomes fy nhad (my father), ei dad (his father), ei thad (her father)). There are three main types: soft, nasal, and aspirate mutations, each triggered by specific grammatical conditions. English has no equivalent.

- Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) Order: Unlike English’s SVO (Subject-Verb-Object) order, Welsh typically places the verb first (e.g., Mae’r dyn yn siarad – Is the man speaking – "The man is speaking").

- Lack of Indefinite Articles: Welsh doesn’t have words for "a" or "an." Car can mean "car" or "a car."

- Prepositions: Welsh uses prepositions more extensively than English, often creating idiomatic expressions (e.g., dw i’n mynd i’r ysgol – "I am going to the school").

- Gender: Nouns in Welsh are either masculine or feminine, impacting mutations and agreement with adjectives, a feature largely lost in modern English.

3. Vocabulary:

- While Welsh has borrowed words from Latin and English over centuries (e.g., ffenestr from Latin fenestra for window, bws from English ‘bus’), its core vocabulary remains distinctly Celtic. This means that a speaker of English will find very few cognates with Welsh words, making vocabulary acquisition a significant challenge for learners.

The Contemporary Landscape: Challenges and Aspirations

Despite the remarkable revival, the Welsh language still faces considerable challenges in the shadow of English, a global lingua franca.

- Globalization and Media: The sheer volume of English-language media, entertainment, and digital content presents a constant pressure.

- Inward Migration: Many people move to Wales without learning Welsh, altering the linguistic balance in some areas.

- Active Use: While many learn Welsh in school, ensuring its active use in homes, workplaces, and social settings beyond formal education remains crucial.

The Welsh Government has set an ambitious target of reaching one million Welsh speakers by 2050 (from around 560,000 in 2021). This goal is being pursued through continued investment in Welsh-medium education, support for Welsh language initiatives in communities (Mentrau Iaith), promotion of the language in the workplace, and leveraging technology to make learning and using Welsh more accessible. Online resources, apps, and social media platforms are playing an increasingly important role in connecting learners and speakers.

Conclusion

The journey from English to Welsh, both historically and linguistically, is a profound narrative of divergence, suppression, and ultimately, a triumphant resurgence. The Welsh language is more than just a means of communication; it is the living heart of Welsh identity, a cultural treasure that connects contemporary Wales to its ancient past. While English remains the dominant language of the UK and often the primary language for many in Wales, the Cymraeg continues to carve out its vital space. The ongoing efforts to protect, promote, and expand the use of Welsh are a powerful testament to the resilience of a nation determined to keep its unique tongue not just alive, but thriving, ensuring that the distinctive sounds of Cymraeg will continue to echo across the hills and valleys of Wales for generations to come.