Languages, at first glance, appear to exist on a flat plane, each a unique and complete system for human communication. Every language, from the most widely spoken to the critically endangered, possesses its own intricate grammar, rich vocabulary, and cultural nuances. However, a deeper examination reveals a complex, often invisible, stratification – a "language hierarchy" that significantly influences their status, survival, and the lives of their speakers. This hierarchy is rarely about linguistic superiority but rather a reflection of socio-political power, economic influence, historical events, and cultural dominance.

This article will delve into the multifaceted concept of language hierarchy, exploring its various dimensions: from linguistic classifications and social prestige to global dominance and the profound implications for communities and individuals.

1. The Linguistic Hierarchy: Family Trees and Classification

At its most fundamental level, "language hierarchy" can refer to the systematic classification of languages into families, branches, and sub-branches based on shared ancestry. This is a descriptive hierarchy, rooted in historical linguistics, and it does not imply any inherent value judgment. For instance, the Indo-European language family is a vast supergroup, encompassing Germanic languages (English, German), Romance languages (Spanish, French, Italian), Slavic languages (Russian, Polish), Indo-Aryan languages (Hindi, Bengali), and many others.

Within these families, languages branch out. For example, Proto-Germanic evolved into West Germanic (English, German, Dutch) and North Germanic (Swedish, Danish, Norwegian). This tree-like structure is a scientific tool for understanding linguistic evolution and relationships, akin to a biological taxonomy. While crucial for linguists, this form of hierarchy is distinct from the social and political stratification that more commonly defines the term in public discourse. It provides the foundational understanding of how languages are related but doesn’t explain why some languages thrive while others falter.

2. The Social and Political Hierarchy: Official Status and Prestige

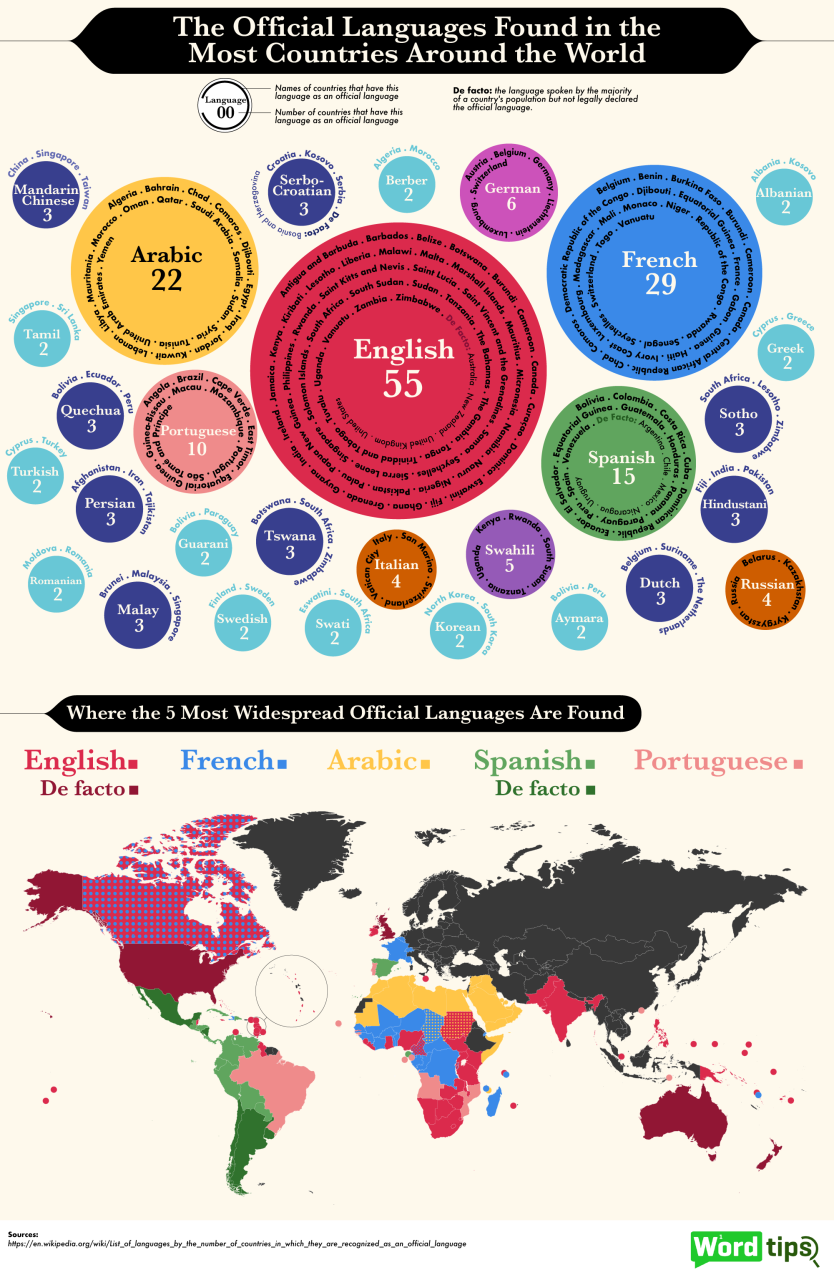

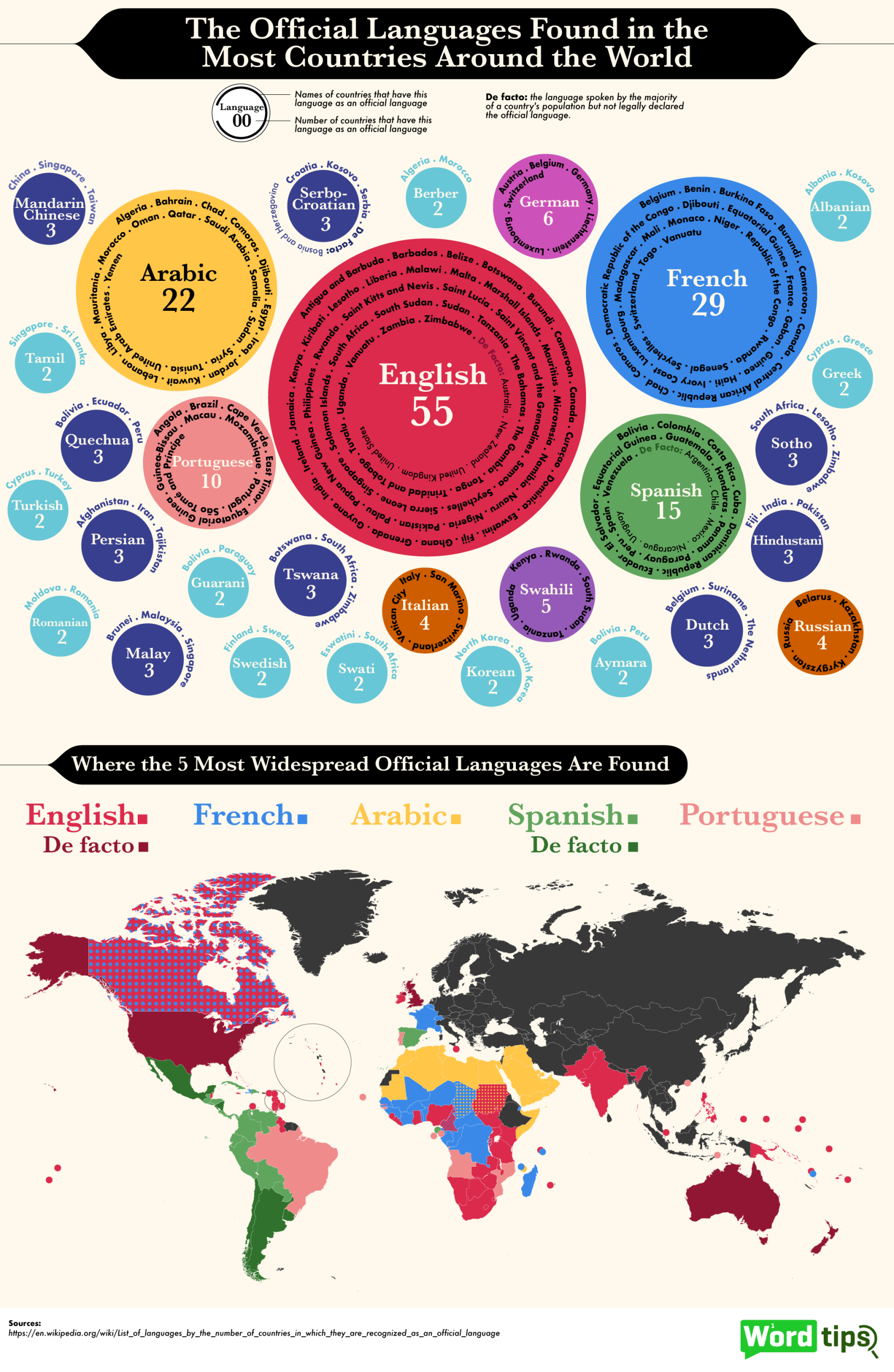

The most palpable form of language hierarchy emerges from social and political contexts. Governments often designate "official languages" for administrative purposes, legal proceedings, education, and public communication. This conferral of official status immediately elevates a language above others within a given territory. For example, in India, Hindi and English are official languages at the federal level, but numerous other languages are recognized as official in specific states, creating a complex linguistic mosaic with varying degrees of official recognition and practical utility.

Official vs. National Languages: While an official language serves governmental functions, a "national language" often embodies a nation’s identity and culture, even if it lacks full official status. In some cases, like French in France or Japanese in Japan, the national and official language are the same. In others, like Māori in New Zealand, it holds national significance and increasingly official recognition, but English remains dominant in many spheres.

Minority Languages and Dialects: Below the official or national languages often lie a multitude of minority languages and regional dialects. These languages, though vibrant and culturally rich for their speakers, typically receive less government support, fewer educational resources, and limited presence in media. Their speakers may face pressure to assimilate into the dominant linguistic group, leading to language shift across generations.

The famous adage attributed to Max Weinreich, "A language is a dialect with an army and a navy," perfectly encapsulates this dimension of hierarchy. The distinction between a "language" and a "dialect" is often more a matter of political power and social prestige than purely linguistic difference. Varieties spoken by powerful groups tend to be codified, standardized, and elevated to "language" status, while those spoken by less powerful groups may be relegated to "dialect" status, often implying inferiority or lack of proper form. Standard forms of a language (e.g., Standard English, High German) also sit atop a hierarchy, often perceived as more ‘correct’ or prestigious than regional variants or vernaculars.

3. The Economic and Global Hierarchy: Lingua Francas and Digital Dominance

In an increasingly interconnected world, economic power and global influence profoundly shape language hierarchy. Languages associated with powerful economies and dominant geopolitical actors tend to gain international prominence as lingua francas – common languages used by people who speak different native languages.

English as the Global Lingua Franca: Currently, English stands at the apex of this global hierarchy. Its historical spread through the British Empire, followed by the economic and cultural dominance of the United States in the 20th and 21st centuries, has cemented its position. English is the primary language of international business, science, technology, aviation, diplomacy, and popular culture (film, music). Proficiency in English is often seen as a prerequisite for global careers, access to higher education, and participation in international discourse, creating significant advantages for native English speakers and immense pressure on others to learn it.

Regional Lingua Francas: Beyond English, other languages hold significant regional lingua franca status. Spanish is crucial across Latin America and increasingly important in the United States. Arabic unites a vast swathe of the Middle East and North Africa. Mandarin Chinese is gaining international economic clout, particularly in Asia and Africa. Swahili serves as a vital bridge language across East Africa. French maintains its role in diplomacy and across many parts of Africa. These languages facilitate trade, communication, and cultural exchange within their respective spheres of influence.

Digital Dominance: The digital age has introduced another layer to this hierarchy. Languages with more content available online, more software and operating system support, and larger online communities tend to be more "visible" and accessible in the digital realm. While efforts are underway to make the internet more multilingual, a significant portion of its content and infrastructure remains dominated by a handful of languages, primarily English. This digital divide further entrenches the hierarchical positions of languages, offering more opportunities for engagement and innovation to speakers of dominant digital languages.

4. The Educational and Media Hierarchy: Access and Opportunity

The language of instruction in educational systems is a critical determinant of a language’s status. In many post-colonial nations, the language of the former colonizer (e.g., English, French, Spanish) remains the primary medium of instruction, especially in higher education and specialized fields. This often marginalizes indigenous languages, which may only be used in primary education or not at all. Students whose native language differs from the language of instruction face significant hurdles, potentially impacting their academic performance and future opportunities.

Similarly, the media landscape reflects and reinforces language hierarchies. Dominant languages saturate television, radio, film, music, and publishing. Major global news outlets, scientific journals, and popular entertainment are primarily produced in these languages. This creates a cultural imbalance, where the narratives, perspectives, and cultural products of dominant language groups are widely disseminated, while those of minority languages remain largely confined to local audiences or face challenges in reaching broader visibility. Access to information, knowledge, and cultural expression becomes stratified by language.

5. Consequences and Challenges of Language Hierarchy

The existence of language hierarchy brings forth a myriad of consequences, both beneficial and detrimental:

- Language Endangerment and Loss: Perhaps the most severe consequence is the accelerated rate of language endangerment and extinction. As dominant languages offer more economic and social opportunities, speakers of minority languages, especially younger generations, may abandon their ancestral tongues. This loss represents an irreplaceable erosion of human knowledge, cultural diversity, and unique worldviews embedded within each language.

- Cultural Homogenization: The dominance of a few languages can lead to a homogenization of culture, as diverse forms of expression are either translated (and potentially diluted) or simply overshadowed.

- Unequal Access and Opportunity: Language barriers create significant disparities in access to education, employment, healthcare, and justice. Individuals who do not speak the dominant language face systemic disadvantages, limiting their social mobility and civic participation.

- Identity Struggles: For speakers of minority languages, the hierarchical pressure can lead to identity conflicts, a sense of marginalization, or the difficult choice between preserving heritage and pursuing opportunities.

- Cognitive Advantages of Multilingualism (for the privileged): While the pressure on minority language speakers is often negative, the voluntary learning of dominant languages by others can lead to cognitive benefits associated with multilingualism, such as enhanced problem-solving skills and cultural understanding. However, this is often a choice made from a position of relative stability, not a necessity for survival.

6. Counter-Movements and the Pursuit of Linguistic Diversity

Recognizing the profound implications of language hierarchy, various efforts are underway to counter its homogenizing effects and promote linguistic diversity:

- Language Revitalization Programs: Communities and governments are investing in programs to document, teach, and revive endangered languages, aiming to reverse language shift and reconnect younger generations with their linguistic heritage.

- Multilingual Education: Advocating for educational systems that support both national/official languages and minority languages, fostering true multilingualism rather than linguistic assimilation.

- Digital Inclusion: Initiatives to create more digital content, software, and tools in a wider array of languages, ensuring that the benefits of the internet are accessible to all.

- Policy and Advocacy: International bodies like UNESCO, alongside numerous NGOs and academic institutions, advocate for linguistic rights, encourage the protection of linguistic diversity, and support multilingualism as a global asset.

- Valuing Diversity: A growing recognition that linguistic diversity is a fundamental aspect of human heritage, analogous to biodiversity, and that each language offers a unique lens through which to understand the world.

Conclusion

The concept of language hierarchy is a complex and dynamic phenomenon, far removed from any inherent linguistic quality. It is a social construct, shaped by centuries of political power, economic shifts, historical conquests, and technological advancements. While the linguistic classification of languages is a neutral scientific endeavor, the social, political, and economic hierarchies imbue languages with varying degrees of prestige, utility, and vulnerability.

Understanding these hierarchies is crucial for appreciating the challenges faced by countless linguistic communities worldwide and for fostering a more equitable and diverse global landscape. The ongoing push for language preservation, multilingual education, and digital inclusion represents a collective effort to recognize the intrinsic value of every language, ensuring that the stratified tongue ultimately speaks with a multitude of voices.