The question "Is French a Latin language?" might seem straightforward to linguists, but for many, particularly those new to the intricacies of language evolution, it can spark curiosity. While its melodic pronunciation and unique nasal vowels might set it apart from its Romance cousins like Italian or Spanish, the unequivocal answer is yes: French is, at its very core, a Latin language. It is a direct descendant of Vulgar Latin, the everyday spoken language of the Roman Empire, which evolved over centuries into the rich, complex tongue we know today.

To understand French’s Latin heritage, we must embark on a journey through history, tracing its lineage back to the Roman conquest of Gaul, examining the forces that shaped its development, and dissecting its linguistic features that bear an unmistakable Latin imprint.

The Cradle of Romance: Vulgar Latin in Gaul

The story of French begins with the expansion of the Roman Empire. By the 1st century BCE, Julius Caesar had conquered Gaul, the territory encompassing modern-day France, Belgium, and parts of Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands. With Roman rule came Roman culture, administration, and, crucially, the Latin language. However, it wasn’t the Classical Latin of Cicero or Virgil that took root among the Gauls. Instead, it was Vulgar Latin (Latin vulgus meaning "the common people") – the informal, colloquial speech of soldiers, merchants, administrators, and colonists.

Vulgar Latin differed significantly from its classical counterpart. It was less grammatically complex, more pragmatic, and varied regionally. As Roman soldiers and settlers intermingled with the indigenous Celtic-speaking Gauls, a process of linguistic assimilation began. The Gauls gradually abandoned their native Celtic languages in favor of Vulgar Latin, which became the lingua franca of the region.

The distance from Rome, coupled with the existing linguistic substratum of Gaulish Celtic (which exerted some influence, though often subtle, on pronunciation and possibly certain idiomatic expressions), meant that the Vulgar Latin spoken in Gaul began to diverge from the Latin spoken in Italy, Iberia, or Dacia. This regional differentiation was the first crucial step in the birth of the Romance languages, of which French is a prominent member.

From Gaul to France: Early Evolution and Influences

The fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE brought about significant changes. Gaul was invaded by various Germanic tribes, most notably the Franks. The Franks, who eventually gave France its name, established dominance over the region. While they initially spoke a Germanic language (Old Frankish), they gradually adopted the Gallo-Roman vernacular spoken by the majority population.

However, the Frankish influence was not negligible. This period, roughly from the 5th to the 9th centuries, saw the emergence of Old French, a language that was still recognizably Latin-derived but had undergone profound transformations. The Frankish superstratum introduced a significant number of Germanic loanwords into the vocabulary, particularly terms related to warfare, administration, colors, and certain abstract concepts (e.g., guerre "war" from Germanic werra, blanc "white" from blank, choisir "to choose" from kausjan). More subtly, Frankish might have contributed to certain phonological shifts, such as the initial /h/ sound in some words (though its exact impact is debated).

By the 9th century, the linguistic divergence between Latin and the emerging Romance vernaculars was so pronounced that mutual intelligibility was largely lost. The Oaths of Strasbourg (842 CE), a political alliance between two grandsons of Charlemagne, are often cited as the earliest written document in a distinct Romance language, showcasing an early form of French that was no longer Latin.

Linguistic Evidence: The Unmistakable Latin Core

Despite centuries of evolution and external influences, French proudly displays its Latin DNA in its fundamental linguistic structures:

-

Vocabulary: This is perhaps the most obvious link. A vast majority of French words trace their etymology directly back to Latin. While pronunciation and spelling have changed dramatically, the roots are clear:

- Latin aqua > French eau (water)

- Latin homo > French homme (man)

- Latin cantare > French chanter (to sing)

- Latin mare > French mer (sea)

- Latin femina > French femme (woman)

- Latin amicus > French ami (friend)

- Latin tempus > French temps (time, weather)

French also exhibits doublets, pairs of words derived from the same Latin root but entering the language at different times or through different routes. One word is often a "popular" descendant, evolving naturally through sound changes, while the other is a "learned" borrowing, often re-introduced directly from Classical Latin during periods of scholarship or religious influence. For example:

- Latin fragilis > popular frêle (frail) / learned fragile (fragile)

- Latin hospitalis > popular hôtel (hotel) / learned hôpital (hospital)

- Latin rationem > popular raison (reason) / learned ration (ration)

-

Grammar: The grammatical backbone of French is undeniably Latinate.

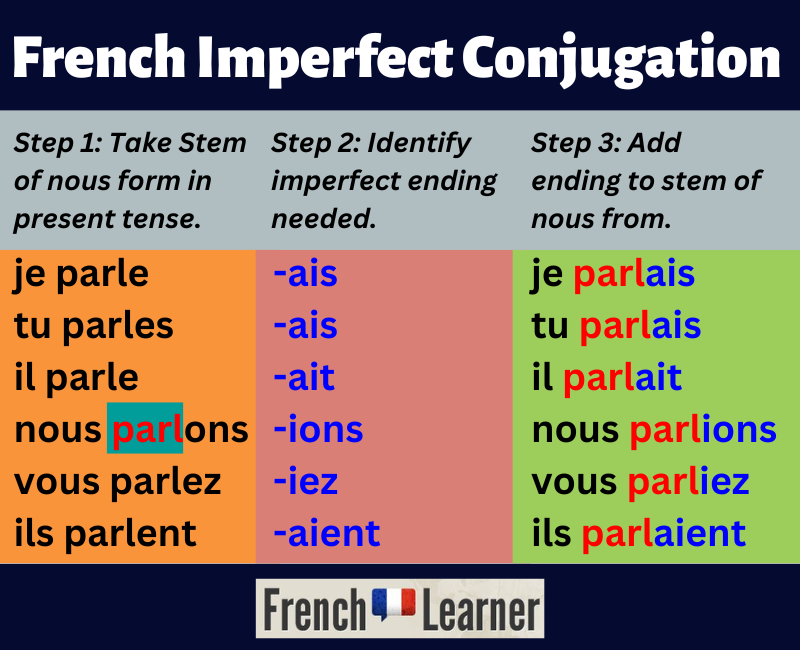

- Verb Conjugation: French verbs retain a complex system of conjugations for tense, mood, and person, a direct inheritance from Latin. While the Latin passive voice largely disappeared, and new compound tenses emerged (e.g., passé composé formed with avoir or être + past participle, mirroring Latin perfect tenses in function), the fundamental structure of inflecting verbs remains.

- Noun Gender: French nouns are assigned a grammatical gender (masculine or feminine), a direct continuation of Latin’s gender system (though Latin also had a neuter gender, which largely merged into masculine in Romance languages).

- Pronoun System: The elaborate system of personal pronouns (subject, direct object, indirect object) mirrors the Latin pronominal structure, albeit with significant simplification from Latin’s case system.

- Syntax: While Latin had a more flexible word order due to its case system, French, like most Romance languages, settled into a relatively strict Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) order, though still exhibiting some Latinate influences in areas like adjective placement or subordinate clauses.

- Prepositions: The loss of most of Latin’s case endings led to an increased reliance on prepositions (e.g., de, à, pour) to express grammatical relationships, a common development across Romance languages.

-

Phonology: While French pronunciation has diverged significantly from Latin, the changes were systematic and can be traced through established linguistic rules.

- Vowel Shifts: Latin vowels underwent significant changes, leading to the development of French’s characteristic oral and nasal vowels.

- Consonant Changes: Intervocalic consonants often weakened or disappeared (e.g., Latin vita > French vie). Final consonants in many words became silent (e.g., Latin tempus > French temps /tɑ̃/).

- Loss of Unstressed Syllables: Latin’s initial and medial unstressed syllables were often reduced or dropped, leading to shorter French words (e.g., Latin hospitalem > French hôpital).

These systematic transformations, rather than random alterations, are precisely what define a language’s evolution from its ancestor.

Beyond Latin: Other Influences on French

While Latin forms the bedrock, French, like any living language, has absorbed influences from various sources throughout its history:

- Gaulish (Celtic): As the substratum language, Gaulish likely contributed a handful of words (e.g., chêne "oak," boue "mud") and perhaps some subtle phonological features or intonation patterns, though its direct lexical impact is relatively small.

- Frankish (Germanic): As discussed, this superstratum had a significant lexical impact (hundreds of words) and possibly influenced phonology and word order.

- Old Norse: The Norman Conquest of England in 1066, led by William the Conqueror (a Duke from Normandy, a region in France), brought a dialect of Old French to England. The Normans themselves had Viking (Norse) ancestry, and Old Norse had contributed some words to Norman French, which then found their way into English. However, its direct impact on the French spoken in mainland France was limited.

- Italian: During the Renaissance, Italian culture flourished, and French borrowed numerous terms related to art, music, finance, and cuisine (e.g., balcon, opéra, banque, cuisine).

- Arabic: Through contact during the Crusades and via Arab scholarship in medieval Spain, French acquired some Arabic loanwords, particularly in scientific and commercial domains (e.g., sucre "sugar," algèbre "algebra").

- English: In more recent centuries, especially since the 20th century, English has become a significant source of loanwords, particularly in technology, business, and popular culture (e.g., le weekend, le parking, un email).

Crucially, these influences, while enriching and diversifying the French lexicon, have not fundamentally altered its Latin grammatical structure or its core vocabulary. They are layers added to an already robust Latin foundation.

Modern French and its Romance Identity

Today, French stands as one of the most widely spoken languages in the world, an official language in numerous countries, and a cornerstone of diplomacy and culture. Its distinct sounds, including its renowned nasal vowels (e.g., un, on, en) and the uvular "r" (e.g., Paris), are products of its unique phonological evolution from Latin, setting it apart from, say, the more open vowels of Italian or Spanish.

Despite these unique features, French shares a deep and undeniable kinship with its Romance sister languages. Speakers of French, with some effort, can often grasp the meaning of Spanish, Italian, or Portuguese texts, and vice versa, due to the shared Latin vocabulary and grammatical principles. This mutual intelligibility, however limited in its spoken form, is a testament to their common ancestry.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the answer to "Is French a Latin language?" is an emphatic yes. French is a Romance language, a direct and continuous evolution of the Vulgar Latin spoken in Roman Gaul. While it has been profoundly shaped by centuries of historical, cultural, and linguistic interactions – notably the significant influence of Germanic Frankish tribes – its essential character, its grammatical framework, and the vast majority of its core vocabulary remain rooted in Latin.

French is a magnificent example of linguistic evolution, a testament to how a language can transform over millennia, absorbing new influences while retaining its fundamental identity. Its Latin heart beats strong, making it a powerful link to the Roman past and a vital member of the Romance language family.