The concept of an "enemy" is a universal human experience, deeply embedded in our psychology, history, and language. Across cultures, the "other" – the adversary, the rival, the foe – serves to define identity, forge alliances, and shape narratives of conflict and resolution. In the Spanish language and the rich tapestry of Hispanic cultures, the term "enemigo" (and its feminine form, "enemiga") is far more than a simple translation of the English word. It is a concept imbued with historical weight, nuanced linguistic expressions, and profound cultural significance, reflecting centuries of struggle, passion, and artistic expression.

This article will delve into the comprehensive understanding of "enemigo" in Spanish, exploring its etymology, semantic range, idiomatic expressions, and its manifestation in the historical, political, literary, and cultural landscapes of the Spanish-speaking world.

I. The Linguistic Foundation: "Enemigo" and Its Kin

At its core, the Spanish word "enemigo" derives from the Latin inimicus, meaning "unfriendly" or "not a friend." This etymological root immediately highlights the relational aspect of enmity: an enemy is defined by the absence or inversion of friendship.

Gender and Number: Like all Spanish nouns, "enemigo" is gendered.

- Enemigo: Masculine singular (e.g., un enemigo peligroso – a dangerous enemy)

- Enemiga: Feminine singular (e.g., una enemiga acérrima – a bitter enemy)

- Enemigos: Masculine plural (can also refer to mixed-gender groups)

- Enemigas: Feminine plural

Common Adjectives and Modifiers: The intensity and nature of enmity are often conveyed through specific adjectives:

- Enemigo acérrimo: A bitter, staunch, or sworn enemy.

- Enemigo declarado: An open, declared enemy.

- Enemigo mortal: A mortal enemy, implying a fight to the death or extreme hatred.

- Enemigo común: A common enemy, unifying disparate groups.

- Enemigo público: Public enemy, often used for notorious criminals.

- Enemigo íntimo: An "intimate enemy," a paradoxical term suggesting a close relationship tainted by animosity, or perhaps an internal struggle.

- El enemigo invisible/silencioso: The invisible/silent enemy, often referring to abstract threats like disease, poverty, or a hidden adversary.

Related Verbs and Nouns:

- Enemistar: To make enemies, to set people against each other. (La política los enemistó. – Politics made enemies of them.)

- Enemistad: Enmity, hostility, animosity. (La enemistad entre las familias duró siglos. – The enmity between the families lasted centuries.)

II. Shades of Opposition: Synonyms and Nuances

While "enemigo" is the primary term, Spanish offers a rich vocabulary to describe various forms of opposition, each carrying distinct connotations:

- Adversario / Oponente / Contendiente: These terms are often used in contexts of competition, debate, or formal conflict (sports, legal battles, political campaigns). They suggest a structured opposition rather than deep personal hatred. (El equipo derrotó a su adversario. – The team defeated its adversary.)

- Rival: Implies competition, often for a shared goal or status, but not necessarily outright malice. Rivals can even share a mutual respect. (Son rivales en los negocios, pero amigos en la vida personal. – They are rivals in business, but friends in personal life.)

- Antagonista: Primarily used in literature and drama to refer to the character who opposes the protagonist. It signifies a fundamental conflict of goals or values. (El villano era el antagonista principal de la historia. – The villain was the story’s main antagonist.)

- Detractor: Someone who criticizes or speaks against a person, idea, or project. This implies verbal opposition rather than physical confrontation. (Sus detractores intentaron desacreditarlo. – His detractors tried to discredit him.)

- Contrario: A more general term for something opposite or adverse. (El viento contrario dificultó la navegación. – The contrary wind made navigation difficult.)

- Némesis: Borrowed from Greek mythology, it refers to an inescapable and formidable opponent, often one’s undoing. (El detective finalmente se enfrentó a su némesis. – The detective finally faced his nemesis.)

- Hostil: An adjective describing an unfriendly or aggressive state, person, or environment. (La multitud se volvió hostil. – The crowd became hostile.)

The choice among these terms depends heavily on the specific context and the nature of the opposition, allowing for precise expression of different kinds of conflict.

III. Idiomatic Expressions and Proverbs: Wisdom of Enmity

Spanish is rich in idiomatic expressions and proverbs that illuminate the cultural understanding of enemies:

- Ser su propio enemigo: To be one’s own worst enemy. This common phrase points to self-sabotage or destructive internal patterns.

- Hacer enemigos: To make enemies.

- Echar un enemigo a la espalda: To get rid of an enemy.

- El enemigo de mi enemigo es mi amigo: The enemy of my enemy is my friend. A classic strategic maxim.

- A enemigo que huye, puente de plata: To a fleeing enemy, a bridge of silver. This proverb advises against pursuing a defeated or retreating foe, suggesting it’s better to let them go than risk further conflict. It emphasizes pragmatism and avoiding unnecessary battles.

- En casa del herrero, cuchillo de palo; en la del enemigo, puñal de acero: In the blacksmith’s house, a wooden knife; in the enemy’s, a steel dagger. This highlights the paradox that one might be poorly equipped in one’s own domain, but face formidable opposition from an enemy.

- Donde hay patrón no manda marinero, ni enemigo de la casa hace agujero: Where there is a master, a sailor doesn’t command, nor does an enemy of the house make a hole. This proverb speaks to the dangers of internal threats and the importance of loyalty.

These expressions reflect a pragmatic, sometimes cynical, and often insightful view of human conflict and the dynamics of enmity.

IV. Historical and Political Dimensions

The concept of "enemigo" has been a powerful force throughout Spanish history, shaping its identity and trajectory:

- The Reconquista (711-1492): For nearly eight centuries, the Iberian Peninsula was defined by the struggle between Christian kingdoms and Muslim rulers. The "Moors" were often cast as the "enemies of the faith" (enemigos de la fe), a religiously and culturally charged designation that justified military campaigns and shaped national identity.

- The Spanish Inquisition: This institution, established in 1478, sought to identify and suppress "enemies of the Church" (enemigos de la Iglesia) and "enemies of the Crown" (enemigos de la Corona), targeting conversos (Jews converted to Christianity), moriscos (Muslims converted to Christianity), Protestants, and others deemed heretical or subversive. The "enemy" here was internal, often hidden, and ideologically defined.

- Colonialism and Empire: During the Age of Exploration, indigenous populations in the Americas were often viewed and treated as "enemies" by the Spanish conquistadors, justifying conquest and subjugation. European rivals (England, France, Netherlands) were also consistently "enemigos" in the global struggle for power and resources.

- The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939): This was perhaps the most visceral and tragic manifestation of internal enmity. Republicans and Nationalists viewed each other as existential threats, leading to profound ideological divisions, brutal conflict, and a legacy of deep-seated animosity that reverberated for decades. The term "enemigo" was used with intense personal and political hatred by both sides.

- La Leyenda Negra (The Black Legend): This historical narrative, often propagated by Spain’s Protestant rivals, painted Spain as a uniquely cruel, fanatical, and oppressive power. In this context, Spain itself became the "enemy" in the eyes of other European nations, highlighting how external perceptions can construct an "enemy" image.

- Modern Politics: In contemporary Spanish-speaking nations, political discourse frequently employs the term "enemigo" to demonize opposing parties or ideologies, contributing to polarization and often hindering constructive dialogue. The "enemigo político" is a familiar figure in national debates.

V. Cultural and Literary Reflections

The figure of the enemy, in all its forms, permeates Spanish and Latin American culture, art, and literature:

-

Literature:

- Don Quijote: Cervantes’ masterpiece offers a profound exploration of imagined enemies. Don Quijote famously charges windmills, believing them to be giants. This illustrates the idea of an enemy as a projection of one’s own internal struggles, delusions, or ideals. He also confronts "enemies" of chivalry and injustice, highlighting a noble, if misguided, opposition.

- Lazarillo de Tormes: This picaresque novel presents a world where hunger, poverty, and cruel masters are the protagonist’s constant "enemies," showcasing a more societal and systemic form of adversity.

- Federico García Lorca: In his tragedies like Bodas de Sangre (Blood Wedding), characters are often driven by fate, honor, and deep-seated grudges, where family feuds and ancestral "enemistad" lead to inevitable tragedy. The enemy can be a person, but also an abstract force like destiny or social norms.

- Gabriel García Márquez: In works like Cien Años de Soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude), the recurring cycles of war, political upheaval, and family feuds present "enemigos" that are both personal and historical, often tied to the very fabric of the community.

-

Sports: El Clásico, the rivalry between Real Madrid and FC Barcelona, is a prime example of ritualized enmity. While players and fans can be passionate, the "enemigo" status is often a source of identity, excitement, and shared cultural experience rather than genuine hatred.

-

Bullfighting (La Tauromaquia): For many, the bull is a magnificent, formidable "enemigo" whose raw power and bravery are respected, even as it is overcome. It’s a complex dance of man versus beast, where the "enemy" is also a symbol of primal force and nobility.

-

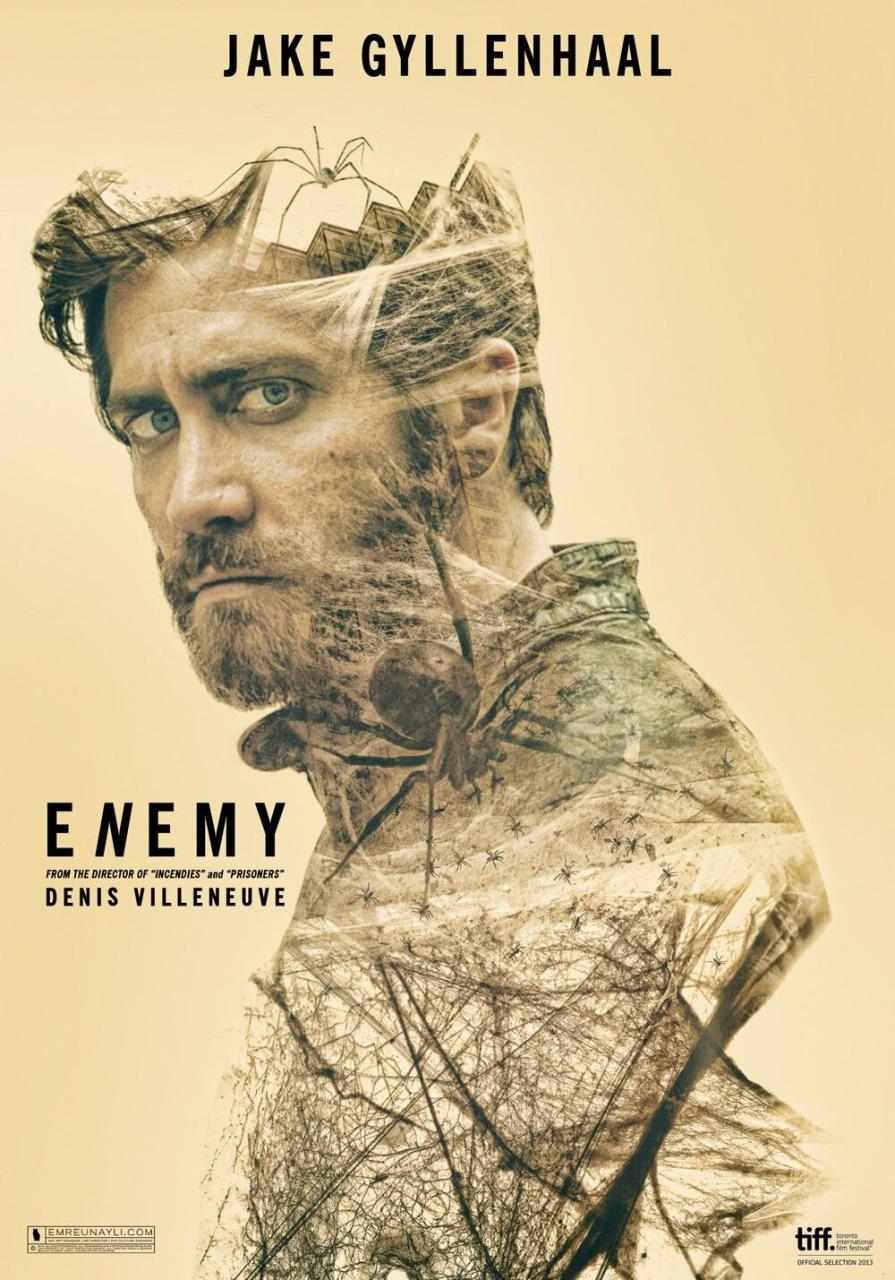

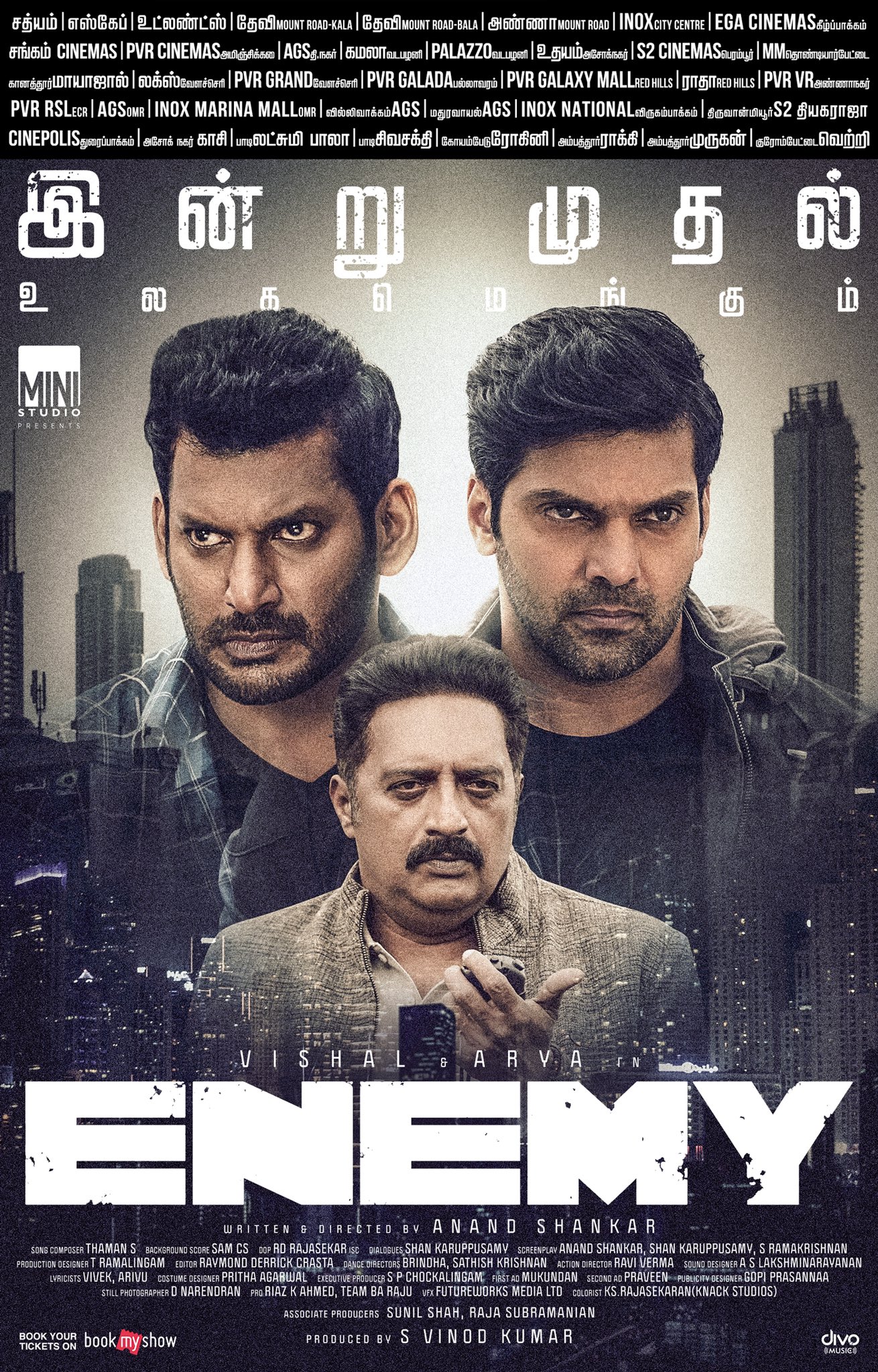

Cinema and Telenovelas: Villains and antagonists are central to the narratives, providing conflict and dramatic tension. The "enemigo" in these popular forms often embodies moral corruption, betrayal, or social injustice, allowing for clear distinctions between good and evil.

VI. The Psychological and Philosophical Undercurrents

Beyond the literal, the concept of "enemigo" in Spanish-speaking cultures often touches upon deeper psychological and philosophical themes:

- The "Other": The enemy helps define "us." By identifying what we are against, we solidify what we stand for. This "othering" can be a source of solidarity within a group, but also a dangerous path to dehumanization.

- Identity and Conflict: Many cultures, including Hispanic ones, have narratives where identity is forged through overcoming adversity or confronting a powerful foe. The struggle against an enemy can be seen as a crucible for character.

- Honor and Vengeance: In some traditional contexts, particularly in rural or historically stratified societies, the concept of an enemy is deeply intertwined with honor (honor) and the perceived need for vengeance (venganza) to restore balance or uphold family reputation.

- Reconciliation: Despite the intensity of enmity, Spanish-speaking cultures also possess a strong capacity for reconciliation, often mediated through family, community, or religious institutions, reflecting a desire to move beyond conflict.

Conclusion

The word "enemigo" in Spanish is far more than a dictionary entry; it is a cultural artifact, a linguistic chameleon, and a historical witness. From the echoes of the Reconquista to the passionate cries of a football match, from the internal battles of Don Quijote to the tragic feuds of Lorca’s plays, the concept of the enemy profoundly shapes the Spanish-speaking world. It reflects a nuanced understanding of opposition, competition, hatred, and the complex human need to define oneself in relation to others.

By exploring its etymology, its synonyms, its idiomatic expressions, and its manifestations across history, politics, and culture, we gain a deeper appreciation for how the Spanish language articulates not just conflict, but also identity, values, and the enduring drama of the human condition. The "enemigo" is not merely an adversary; it is an intrinsic part of the narrative of Spanish-speaking peoples, constantly evolving yet forever present.